When people first encounter Silvio Gesell’s proposal for monetary reform — i.e. demurrage, a system in which units of currency lose purchasing power at a predetermined, scheduled rate of depreciation — they often jump to the conclusion that demurrage is equivalent to inflation. “Why do we need demurrage when we already have inflation?” is the most common question people ask when they first hear Gesell’s ideas. But demurrage and inflation are NOT the same thing. Although they have some similarities, they are VASTLY different in terms of how they affect the circulation and distribution of wealth throughout the economy. It is critical to understand these differences.

Before dissecting those differences, let’s briefly restate the rationale for demurrage money in the first place. Gesell’s monetary perspective is built on the fundamental insight that the dual functions of money — medium of exchange and store of wealth — are inherently incompatible. According to Gesell, any instrument that is designed to be stored for long periods of time without cost or loss will systematically fail to circulate whenever there are expectations of falling prices.

In The Natural Economic Order, Gesell wrote, “commerce is mathematically impossible with falling prices.” In other words, if you expect prices to fall, why would you buy something today when you will be able to buy it cheaper tomorrow? If people can store their wealth in a form that allows them to preserve it without effort, cost or loss, whenever prices begin to fall (or are even just expected to fall), holders of money have an incentive to postpone their purchases as much as possible. This causes economic downturns to become self-reinforcing. Prices fall, causing holders of money to postpone purchases, which in turn causes prices to fall even more.

As Gesell writes, “demand [i.e. the offer of money] becomes smaller because it is already too small, and supply [i.e. real goods & services] becomes larger because it is already too large.” This is a completely simple, logical, straightforward description of what happens in a commercial crisis, and Gesell shows how this dynamic is a consequence of the irrational design of money.

So Gesell proposes to remedy this problem by denying holders of money a safe haven during times of economic weakness. Why should holders of money be safe when producers of real goods & services are not? Gesell’s solution is simply to subject money to the same laws of nature that apply to virtually all forms of real wealth.

A producer of corn, a manufacturer of automobiles, a teacher, a construction worker, etc. do not have the luxury of withdrawing from the market and keeping their powder dry anytime there is economic uncertainty. The physical nature of the universe forces them to offer their produce for sale, regardless of the economic environment. And if they fail to do so, the laws of nature punish them.

Therefore, if money is to be an effective medium to facilitate the exchange of real goods & services, it must be subject to the same forces that affect those goods & services. And demurrage accomplishes this. Designing a form of money which loses purchasing power with the passage of time puts money on a level playing field with the goods & services it is used to exchange.

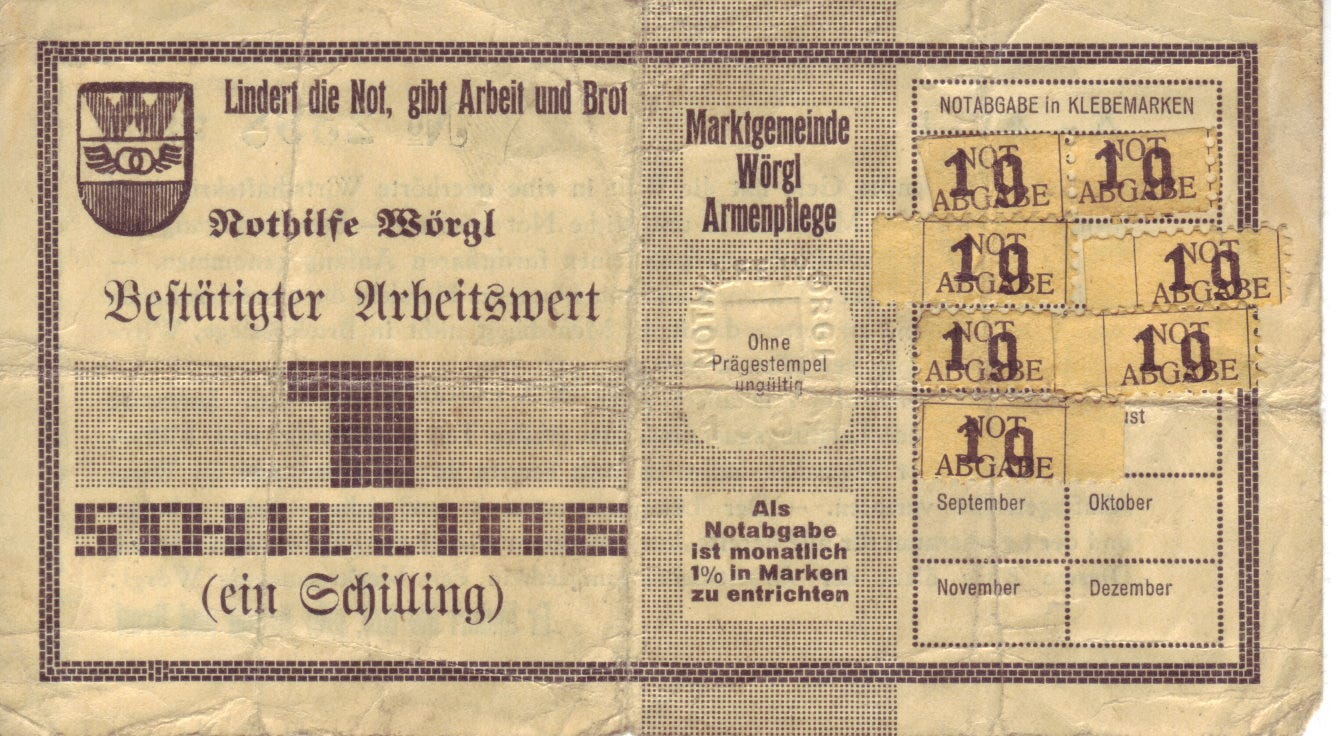

(For a case study of one of the most famous real world implementations of demurrage money, see our article, The Miracle of Wörgl.)

(It should be noted that at the time Gesell initially made this proposal, the only practical way to implement it was via the issuance of physical notes, the holders of which had to purchase stamps periodically and affix them to the notes in order for them to remain valid. Today, such a cumbersome, inconvenient system would not be necessary. All forms of digital money (e.g. bank balances) could have demurrage applied automatically without the holders having to do anything. Whereas physical cash (which today represents a small fraction of the overall money supply) could be subject to demurrage in a variety of ways other than through stamped money. One example would be the issuance of different series of bank notes which periodically expire and need to be exchanged for new series. So the practical challenges of implementing demurrage are much more easily dealt with today than during Gesell’s time.)

So now let’s return to the original question. Does inflation work in the same way, and serve the same purpose, as demurrage? Does inflation impose penalties on holders of money when they withhold it from circulation during periods of falling prices. It obviously does not. All we have to do is consider the definition of the word “inflation” to prove that this is the case.

Inflation is defined as a general rise in the price level. By definition, if prices are falling there is no inflation. So the penalty for withholding money from circulation which inflation provides DISAPPEARS exactly at the times when society most needs money to circulate — i.e. when there is economic uncertainty causing prices to fall. In fact, not only does the penalty disappear, but it actually reverses and becomes a reward. Holders of money get rewarded for withholding their money from circulation during periods of falling prices because they are able to buy the same goods & services at lower prices in the future.

This is the most important difference between demurrage and inflation. There are several other differences as well.

Demurrage is consistent and predictable. If the demurrage rate is, for example, 6% annually, then money loses 1/2% of its purchasing power per month EVERY MONTH, regardless of whether the economy is expanding, contracting or remaining the same. Inflation, on the other hand, is inconsistent and unpredictable. Sometimes it is high, sometimes it is low, and sometimes it is negative (i.e. deflation). So the element of predictability is another important difference between demurrage and inflation. Predictability is a key determinant of productive investment. The less predictability there is, the less likely people are to be willing to commit their resources to long-term projects. So demurrage is superior to inflation in terms of creating conditions under which people are willing to invest in productive enterprise.

Another related difference between demurrage and inflationary fiat money is the effect on the price level. The standard equation in economics for determining the price level is P = MV. This means that, given a certain quantity of goods & services in the marketplace, the price level is determined by the quantity of money outstanding and the velocity with which that money circulates. If the quantity of money remains the same, an increase in the velocity of money will cause prices to rise, and vice versa. But, as we have already discussed, with conventional fiat money (or “hard money”, like gold), the velocity of money is highly dependent on sentiment of money holders. If they expect prices to fall, they will postpone their purchases, causing the velocity of money to fall. Conversely, if they expect prices to rise, they will have a strong incentive to spend money more quickly since it will buy less goods & services in the future, thus causing prices to rise. (It should be noted that with conventional fiat money, expectations have a tendency to become self-fulfilling prophecies.)

So conventional fiat money gives us the worst of both worlds. When prices are falling, it causes prices to fall even more. And when prices are rising, it causes them to rise more. The incentive structure built into conventional fiat money essentially guarantees price instability by amplifying the natural ebb and flow of economic activity. Whereas demurrage is designed to keep the velocity of money as stable and predictable as possible. Therefore, demurrage is far more effective than inflation in terms of maintaining a stable price level.

Lastly, let’s consider the differences between demurrage and inflation in terms of how they affect employers & employees as well as borrowers & lenders.

It is important to note that demurrage operates only on OUTSTANDING UNITS OF CURRENCY, not on newly issued money or money that will be issued in the future, whereas inflation affects both outstanding currency as well as money issued in the future. So with demurrage, if a laborer earns a salary of, say, $50,000 per year, that salary will buy the same quantity of goods & services today, in one year, and in five years (assuming no inflation). Whereas inflation affects the purchasing power of outstanding money as well as future money. 5% demurrage does not diminish what workers can buy with their future paychecks. Whereas 5% inflation means that their future paychecks buy less and less as time goes by.

And, finally, demurrage and inflation have very different impacts on borrowers and lenders. Inflation benefits borrowers at the expense of lenders. If I borrow $100 today at zero interest for one year and there is 5% inflation during that year, the money I repay has less purchasing power than when I borrowed it. Therefore I gain at the expense of the lender.

But what happens to borrowers and lenders as a result of demurrage? If I lend $100 for one year at zero interest, demurrage has no effect on me whatsoever. If prices remain the same, the $100 I receive in one year will buy the same quantity of goods & services as when I lent the money. So I am no better and no worse off as a result of having lent the money. (For purposes of this article we will ignore so-called “time preference”, which is a questionable concept which says people prefer present consumption to future consumption. We have addressed this subject in an earlier article, which can be found here: Why Does Money Earn Interest? Part One.) The effect of demurrage on borrowers, on the other hand, depends on what they do with the money. If they spend it (either for consumption or investment), they do not bear the cost of demurrage. If they hold onto the money, then yes, they lose due to demurrage, but why would anyone borrow money just to hold onto it?

So, as we see, although there are some superficial similarities, demurrage and inflation are different in a whole host of ways. So the answer to the question, “why do we need demurrage if we already have inflation” should be obvious.

Another big difference is the Cantillon effect. Monetary inflation tends to benefit those closer to money creation (financial institutions, large corporations) while disproportionately eroding everyone else's purchasing power. Whereas demurrage equally pressures every holder to spend, disproportionately eroding the purchasing power of those who hoard.

My concern and question is about saving for a rainy day or saving for other purposes like buying a house. how can one save with demurrage?